“You never change things by fighting the existing reality.

To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

― Buckminster Fuller

While I believe it’s imperative that we stay well informed about what’s happening in the world around us, I believe even more strongly that the time has come to take real action. Let’s build those alternative solutions that Buckminster Fuller, Vaclav Havel and others have talked about. Let’s move from this sublunary world and build the one we all want to live in. We can begin with housing.

This is a long post with lots of photos. I suggest clicking on the title to get the full impact.

current events

Yes, there are some current events that beg to be covered; the release of Epstein’s client list, democratic Colorado removing Trump from the ballot and the upcoming Supreme Court response, other states removing other candidates and how some are trying to make that play into the upcoming movie, Civil War. There is also the wonky thesis of that movie and the predictive programming it telegraphs. Then there is the ever increasing tension between the kulak and the state in the Netherlands and Germany. If I were to predict the outbreak of civil war, I would say the chances of it happening are much higher in those two places than in the US. Compared to the phony manufactured division being created in this country by the lame stream media between political factions, the rift between farmers in those countries and their governments is very real.

But those are all topics that will come and go. What remains are the houses we live in.

Some of you precious readers have been hinting that I should focus more on solutions and less on problems. I agree. Over the past three years I’ve written a few posts here and there that offer solutions, most of them dealing with the topics in my byline; health, housing, textiles, agriculture, food.

I’m not a doctor or a pharmacist. Apart from an injury I suffered from a flu jab in 1971 and overcoming health issues about which the medical industrial complex (MIC) was clueless, I’m not a ‘health professional’. Yet tens of thousands of you read what I write about health, jabs and the MIC. If you appreciate that, then you may like the esoteric things in which I’ve been much more deeply immersed for the past four decades.

So, instead of covering the bad news topics mentioned above, I’m going to continue in the same solutions oriented direction I began in my last post.

onward

Another topic that many fail to consider is housing. Surprisingly, or maybe not surprisingly, because the toxins in modern housing have a lot to do with health issues that many suffer from, housing is not considered problematic by the MIC. When was the last time your doctor suggested that your health problems might be related to the house you live in? Likely… never.

the bigger picture

As alluded in my last post, while managing a five acre grove of avocados in the mid 70’s, I began thinking about how housing, textiles, agriculture, health and food were all once a part of everyone’s daily life. A mere two hundred years ago, all societies essentially revolved around these fundamental areas of human existence. As I began to delve ever deeper into the homesteading lifestyle I found lots of good folks who had carved out home grown niches in these fields. They were doing very well. The idea that this could serve as the basis for a new societal structure began to ferment in my mind.

By the 1980’s the homesteading movement had become such a viable and popular way to escape the matrix that many books and magazines came into being to help guide newbies along (Mother Earth News was once huge). After gobbling up many of those publications for years, I became increasingly nauseated by them. The deeper aspects of homesteading were not being covered. More importantly, as is so often the case with any new, connected, sacred, decentralized trend, the entire movement was being taken over by corporate America. Originally, homesteading meant living a connected life, close to the earth. Everything was done by hand; building a house from local resources, tending a garden by hand, spinning, weaving, tanning ones own livestock hides for clothing, treating illness with diet and native herbs, using food produced on the farm or hunted and gathered nearby, using candles for light and wood for heat.

No globalist machines needed.

Today, homesteading means buying an existing farm, buying a new tractor, buying processed food at the store, being hooked up to the power grid or buying the most modern solar power system, buying all of the most up to date, household electronic widgets, having wifi, cell phones, plasma tv’s and all the rest. Today, homesteading means dragging city trappings to the country. (My local internet provider is my only link to the outside world.)

Today, distinctions between a typical city dwellers house and a modern homesteaders house are nonexistent. This is not what Buckmenster Fuller had in mind when he was talking about building new models that make the problematic old ones obsolete. We’ll never overcome our modern travails by allowing globalists to maintain control of our lives on our homestead. If we want to experience the glee of watching modern syphylization collapse, we need to completely sever all ties to the globalist matrix - especially pertaining to food, health care, clothing and housing (more on housing shortly).

I know, this is a tough pill to swallow, but if simple, little ol’ me can do it, anyone can.

a preface

To lay the ground work for the solutions oriented topics I’ll be writing about in the coming months, I need to inject this preface.

A few of you long time readers may remember that I once had another website where I tried to connect all of this together in a comprehensive lifestyle approach that people could relate to today. I call this lifestyle Krofting. Some of you who have come here from other sites may know my handle from those sites as Krofter. Krofting is my take on the old form of farming still known in the Scottish Highlands today as crofting. Although it wasn’t called crofting everywhere, this land tenure format existed in various formats across the UK and Western Europe for many generations. The tenure was granted by the regional Crown - in some case by the Catholic Church - and was handed down from one generation to the next. As social structures go, it was far from ideal. Indeed, it was just another form of serfdom. Crofters were, for the most part, at the mercy of regional royal families and/or the Catholic church.

However, some of the fundamental aspects of managing a croft were fascinating. A well managed croft never lost any fertility over the course of many generations. In fact, under good management, fertility increased. A knowledgeable father would strive to hand over to his son a more fertile and productive croft than what he inherited.

Another incentive in this regard was pressure from the Crowns local constable - or the local Bishop - who demanded good management of Crown/church land.

An average size croft was around 50 acres. During much of the year the croft would not be able to support all of the crofters livestock, so crofters were able to use Crown commons land for grazing. The commons was typically rougher land not suitable for growing crops.

The commons also provided the local natural resources needed for building the family home - stones for foundations, large tree branches for posts and beams, reed for thatched roofing. The beautiful result was a vernacular architecture that blended perfectly into the landscape… because it came from the landscape.

For the use of these lands, the Crown and the church often extracted exorbitant fees in the form of crops, livestock, fleece and meat.

In the area where I live, something similar exists. My remote rural community is surrounded by millions of acres of wilderness. Most of this land is held by three agencies as a type of commons; the Arizona State Land Department, the US Forest Service and the US Bureau of Land Management. The land is leased to private ranchers for less money than it costs these agencies to manage the land on behalf of the ranchers. Consequently, the land is not managed to improve its quality, it’s managed to maximize profits for the handful of well-to-do ranchers who run cattle ranches at a loss so they can legally write off profits from other businesses on the ranch.

It doesn’t hurt that the Cattleman's Association is one of the oldest and most powerful lobbies in DC.

Wells, ponds (called tanks here), fencing, chaining of invasive species (two bulldozers driving across the landscape with a massive chain tied between them) and firebreaks are all paid for by the various land departments. In other words, the ranching industry is heavily subsidized by taxpayers. Some refer to public lands ranching as welfare ranching.

Like the development of the covid jabs, DEW’s and many other repugnant “private/public partnerships”, the partnership that exists between ranchers and the government is just another form of fascism.

I’m not allowed to run my goats on the millions of acres that surround my farm. But I did glean many of the resources I used to build my cob home from that commons; large Mesquite branches for posts and beams, large Juniper branches for vigas and large beams cut from Douglas Fir trees by a local saw mill.

As the Nobel prize winning economist Elanor Ostrom pointed out, distant managers - in this case the government officials in Phoenix and DC - are clueless about what’s best for the local landscape.

At least the crofters of yesteryear had a local Crown representative or a Bishop who may have had a better understanding of what was best for the local community.

Consequently, over the past one hundred years, the profoundly deep fertility generated by thousands of years of careful management by native Americans has, over the course of a short two hundred years, been destroyed by European grazing and farming practices.

how did all of this come about?

I ended my last post with the sad story of the bulldozing of the five acre avocado grove I had been care-taking and how that coincided with the demise of my relationship with Lupe. Loss of love seems to be a theme in modern agriculture. When we understand how a grove of lovingly planted and cared-for avocados gets bulldozed in favor of short term profits that can be had by covering up that land with ticky tacky houses, then we begin to understand what happened to the rest of the farmland in the US.

Because love was lost, connections to the land were lost. Because connections to the land were lost, connections to Divinity (God) were lost. No Divinity, no soul. No soul, no compassion. Greed, power and control rule the day.

That is how it came about. All of it. End of story.

Not really. The best part is yet to be told.

After the grove was bulldozed and the relationship ended, I moved to the Big Island of Hawaii. Cold. No connections, no contacts, no job prospects.

I brought my mountain bike, snorkeling gear, Hawaiian sling (a simple type of speargun) and a few clothes. Apart from my bike, everything fit in my back pack. I rented a house in Kailua Kona and spent my days exploring the Kona side of the Island on my bike. I developed a routine of riding down the coast to snorkel and spear fish. I became fascinated by the native Hawaiian culture and began sneaking into the luaus at the local resort to watch the native dancers and listen to the native songs being sung.

At that time (early 80’s) it was a short bike ride to get into the native forest. I began to learn the native trees as well as the new invasive species that were already beginning to wreak havoc at that time.

Some time later I bought an old Suzuki Samuri so I could go around the dormant 13,800’ Mauna Kea volcano to explore the other side of the island. After spending some time in and around Hilo I realized I was living on the wrong side of the island. The farmers market in Hilo was already legendary back then. The back to the land movement was well under way there and numerous small farmers were growing a plethora of tropical fruit crops for the market. I made several more trips to Hilo in subsequent years. That market just kept getting better and better.

Because the bamboo housing story evolved over a period of years and has taken up so much of my life, I’m going to combine all my trips to the Big Island in this post. Even at that, there will still be more bamboo stories to tell from Costa Rica, Mexico and where I now live.

back to hilo

After what happened to the avocado grove in California, I initially went to the Big Island entertaining dreams of buying land and setting up a simple homestead from scratch. I found nothing that spoke to me on the Kona side (dryer side) of the island where I was living.

On the Hilo side (wetter side) many areas spoke to me. Even though it sometimes suffered from the wind blowing smoke from active Kīlauea volcano, I loved the Puna district. But the Hāmākua coast took my breath away. Regrettably, the native forest mauna had long ago been laid to waste by the big sugar plantation families. They had also long ago monopolized nearly everything else in Hawaii. That story is too long and complex to go into here.

The short version is that the cultivation of sugar on the Hawaiian islands was subsumed by cheaper labor in less developed countries. The sugar cane fields had all been abandoned. The barren land had been subdivided and was being sold off. Over the years, I looked at a lot of those parcels. Several called to me, but for reasons I cannot put my finger on, I didn’t answer.

I had begun to formulate an idea of what I wanted to do there. I wanted to join the tiny but growing movement in the islands to help make Hawaii more self sufficient in building materials by growing bamboo.

It’s helpful to understand that most building materials in Hawaii come from the mainland, which means they have a lot of embodied energy. Read that, building materials are incredibly expensive in Hawaii.

the bamboo turning point

After watching the avocado grove and the masterful little Japanese home I had been living in get bulldozed into oblivion, I vowed to do something about the misguided polices that allowed that type of craziness to happen. Divine providence soon stepped in and led me to a chance to build adobe homes. That led to building passive solar rammed earth homes, which led to building straw bale homes, which, in a round about way, led me to bamboo.

By then I had come to learn that although the population of the US only represents 4% of the worlds population, we consume 40% of the worlds resources. Much of those resources go into building our grand houses. A lot of research has gone into this phenomenon. Back at that time the average size home in the US was 1,100 square feet. Perhaps the most glaring result of that research was that, if we were to try and house everyone on the planet in the average US house with its average bells and whistles, we would need three more planet earths to supply all of the resources required to do so.

That was then. Here is where we stand today.

Over the last 75 years, the U.S. housing market has undergone a dramatic transformation. Rising productivity, high demand for housing, and new highways built in the wake of World War II pushed many Americans to the suburbs, where homeownership rose and density decreased. The average number of occupants in each home fell, while the average size of a new single-family home ballooned - from just 909 square feet in 1949 to 2,480 square feet in 2021. In 1950, 15.7% of U.S. homes were overcrowded; by 2000 that number had fallen to 5.7%.

The shift towards larger homes was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic when concerns over social distancing and remote work led many to relocate from urban areas to suburban and rural neighborhoods. In one September 2019 survey, 53% of respondents said they preferred to live in a community where the houses are larger and farther apart, with schools, stores, and restaurants several miles away. By July 2021 that figure had risen to 60%.

My second trip to the Big Island was to attend a bamboo conference being sponsored by the Hawaii chapter of the American Bamboo Society. I had been fully immersed in the Society for several years, founding the Southwestern Chapter.

The Hawaii chapter was trying to convince Hawaiian architects and building departments that bamboo was a viable alternative that could help move Hawaii much closer to self sufficiency in building materials. That, in turn, would go a long way toward making housing more affordable. The conference took place over several days with the highlight being the construction of a large poster board that incorporated a number of joinery techniques commonly used in countries where bamboo construction is commonplace.

Four craftsmen from the Hawaiian chapter were in charge of the work. They asked if anyone else from the mainland chapters wanted to participate. I was the only one to hold up a hand. They had no idea of my skill level so they put me to work on the base.

Because I had limited access to bamboo poles I had only done some rudimentary work with bamboo at that point. It quickly became apparent that two of the Hawaiian guys were much more experienced than I was. Although I knew about the complex joinery techniques they were using, I hadn’t yet had access to the fabulous tropical species we were working with.

While we worked, Jules Jahnssen, a Danish fellow who had been commissioned by International Bamboo and Rattan Organization (INBAR) to write a set of international building codes for bamboo, narrated our work for the audience.

about bamboo

I should explain here that using a round, hollow pole to build things requires an entirely different approach to construction that using solid, square or rectangular lumber cut from tree trunks. Or square or rectangular masonry products.

In reality, the only place bamboo becomes an obstacle for use in construction is in ones mind. That became apparent with some of the Hawaiian building authorities that were present.

Here is what I tried to impart.

Bamboo is the largest member of the Gramineae (grass) family. It’s the fastest growing plant on land - only kelp grows faster. Bamboo has a higher tensile strength than mild steel, more flexibility than any other construction material. This makes it the most seismically resistant building material on earth. When used in its natural state, it requires less machining than any other building material. To know it is to love it. It’s a wonderful building material.

back to the demonstration project

Even at that early time, Hawaii already had a good supply of numerous construction grade species of bamboo growing around the islands. Thanks to the work of the Hawaiian chapter of the American Bamboo Society, it now has an abundance of the best construction grade species of bamboo from around the world; Guadua angustifolia from Columbia (considered by many to be the best construction grade bamboo in the world), numerous species of Dendrocalamus, Bambusa, Gigantochloa and Phyllostachys from South East Asia. Plus hundreds of others.

The poster board was constructed in front of an audience of about 80 people. Many were architects and building department officials from all the islands. The press also had a big presence with cameras everywhere and reporters asking us questions during the process.

Some of the building department officials were impressed. Others, not so much. Bias in favor of conventional construction was evident in the questions asked by some of the doubting building officials.

Poster board workshop in Hawaii narrated by Jules Jahnssen, author of the international building code for bamboo. Held on stage in front of large audience of architects and building authorities on the Big Island of Hawaii. Four guys from Hawaii and myself did the actual construction.

My next trip to the Big Island was to attend another, much bigger bamboo conference. This one was sponsored by INBAR in conjunction with the Hawaiian chapter. It took place over three days and involved a number of break-out seminars. There were speakers and presenters from all over the world. My burgeoning interest in using bamboo as a sustainable alternative to conventional construction had me gravitating toward the two primary presenters, both from Columbia; Professor Oscar Hidalgo, who taught bamboo architecture at the University of Columbia at Bogata, and the world famous bamboo architect, Simon Velez.

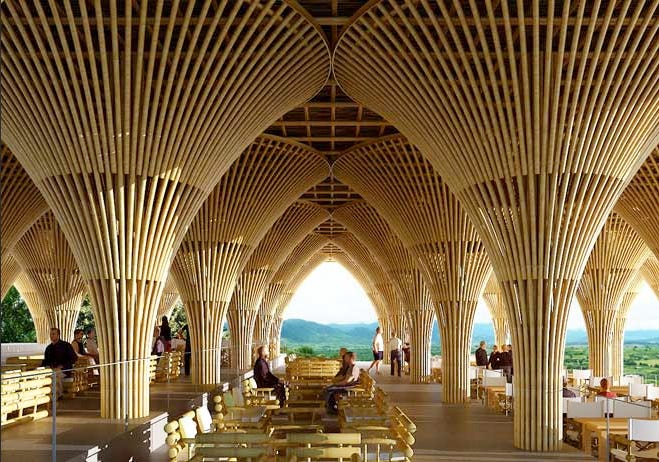

I’m going to leave you with a number of photos of the work of Simon Velez.

Some years later I had the pleasure of hosting Oscar Hidalgo for several weeks in the SW US and Mexico. That’ll be another post.

For all my Spanish speaking readers - a taste of Simon’s brilliant wit.

A wonderful way to do things if secular. As a Christian, and a 'senior senior', I believe we hold similar values

but do things 'hidden in plain sight', right in the face of the matrix, yet we are not in the matrix.

We USE it, pay for it, and it works out.

I too was grieved about your avocado grove. The Bible is very specific when people study it, and at

the very beginning in 'genesis', it says that Elohim (or gods) gave man 'dominion' over the animals,

etc. I'd have to reread it to get it right, as it's been some time.

People NEVER did Dominion correctly. That meant 'take care of them'. That meant 'you're in charge'

and people thought 'money, advantage', 'get ahead'.

Right away going way wrong.

We have the privilege to seek to do things better.

In our little area, we have 'dominion', so the trees, things we grow can depend on us to help them.

And do they EVER try to outdo and show us how much they appreciate the care.

Getting up in years, we can't always DO what we'd like, and we EXPLAIN that to them in our minds,

help them know we CARE nevertheless.

Everything alive, and I include trees, stones, has some 'essence' and we can all tap into this.

You'll find THEY are your friends, won't let you down, won't deceive you. So can I make sure

of the same? Yes, actually, I can.

And so I offer this to readers to expand your communications with the living.

Many people are going 'dead', and you'll find there's little real good discussion

happening in society, and mostly miscommunication.

This is what makes Substack a GIFT, unique.

Let us ALL here take DOMINION of what we're given, and show..whateveryou believe,

God?, the universe?, others? what it's like when we 'give back'.

Thanks for a wonderful discussion, and I totally agree that you have to 'do something else',

which is what we do here.

Stunning photos!! Used to go camping down around Arivaca and Patagonia lake in the late 90's. Lived in Tucson back then. Beautiful country